Over the past seven years, the Obama Administration and Congress have created and funded six new federal evidence-based innovation programs that seek to improve outcomes for young people, their families, and communities all across the country. While these programs vary in design, they share several characteristics: (1) their use of evidence to inform which applicants receive funding; (2) their use of evidence to inform the amount of funding; and (3) their use of rigorous evaluation to determine impact and inform future funding. The five evidence-based innovation programs include:the Social Innovation Fund; the Investing in Innovation Fund; the First in the World Program; the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program; the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program; and the Development Innovation Ventures.[1] Many of these programs are also highlighted in Results for America’s Federal Invest in What Works Index of federal departments and agencies.

TIERED-EVIDENCE APPROACH

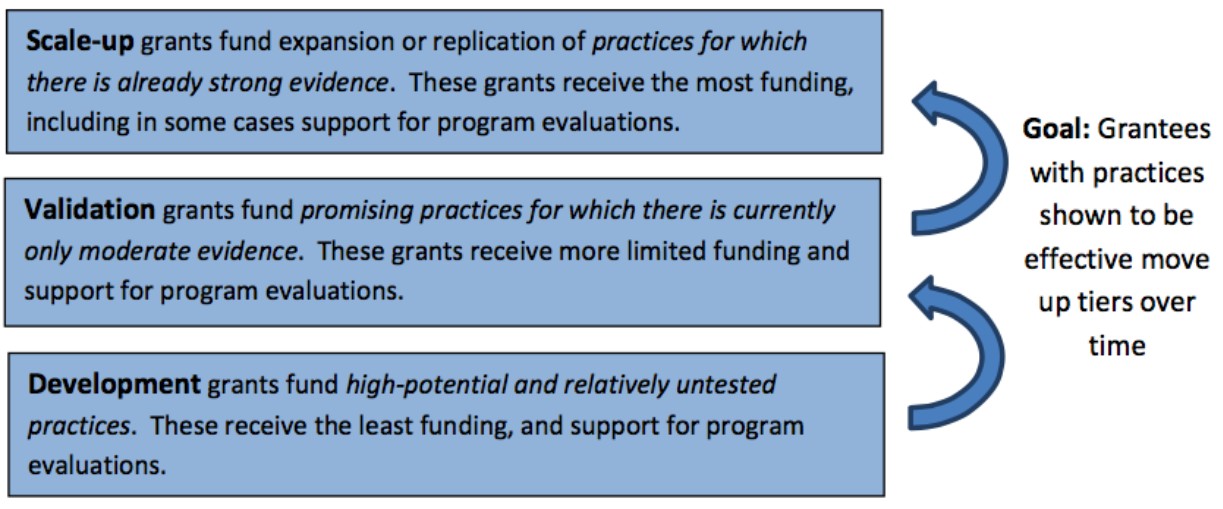

Federal evidence-based innovation programs are commonly anchored by a unique system of grant classification, in which grants are awarded to programs according to their level of evidence of effectiveness. This tiered-evidence framework enables more dollars to be directed towards programs that have demonstrated success and are ready to be scaled for wider impact, while also directing lesser amounts of funding toward interventions that need to be tested and proven. As a result, tiered-evidence grant programs have the goal of identifying evidence-based models that can be replicated. The figure below illustrates this concept.

THE SOCIAL INNOVATION FUND

The Social Innovation Fund (SIF), administered by the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), utilizes public and private resources to grow promising community-based solutions. SIF was funded at approximately $70 million in FY15 and focuses on three priority areas: economic opportunity, healthy futures, and youth development. SIF has two programs: SIF Classic, its original grant program, and SIF Pay for Success (PFS).

SIF Classic funds private intermediary grantmakers that provide grants to subgrantees. Each intermediary is required to match its federal grant dollar-for-dollar, before re-granting funds to subgrantees, which are also required to match funds. Through the match requirements, each project triples its federal investment. In addition, building the evidence base about what works is another key goal of SIF. Currently, evaluations of over 70 SIF-funded programs are underway.[2]

In FY14 and FY15, Congress granted the SIF authority to invest up to 20 percent of its funds in Pay for Success (PFS) initiatives, which totaled approximately $28 million for both years.[3] The SIF PFS program is designed to enhance the capacity of state and local governments, as well as nonprofit organizations, to implement PFS, an innovative contracting model that ties finding for a program to its impact in the community. SIF PFS grantees are required to match their federal grant dollar-for-dollar. In 2014, eight organizations were selected as SIF PFS grantees, receiving grants between $750,000 and $3.6 million for two to three years. More than 40 SIF-funded PFS projects are in various stages of development across the country.[4]

Impact of SIF

Since 2009, CNCS has awarded a total of 43 SIF grants, supporting 279 subgrantees and subrecipients in 41 states and DC, and serving over 400,000 individuals in low-income communities.[5] A 2015 report found that 5 independent, rigorous impact evaluations have found positive effects of SIF-funded work in the areas of workforce training, employment services, personal (income) savings, reading education, and childhood health. Completed evaluation reports can be found on the CNCS Evidence Exchange website. To date, the SIF and its private-sector partners have invested $757 million, $241 million in federal grants and more than $516 million in non-federal match commitments, to benefit the communities it serves.[6]

INVESTING IN INNOVATION FUND

The Investing in Innovation Fund (i3), administered by the U.S. Department of Education (ED), supports innovative and proven approaches that address K-12 education challenges. The goal is to accelerate the development of innovative practices, and to expand the implementation of practices that have a demonstrated impact on improving student outcomes. All i3 grantees must conduct rigorous third-party evaluations to determine their impact, relevant lessons about program design and implementation, and ultimately to identify practices that should be scaled. The i3 program awards grants to school districts and non-profit organizations in partnership with school districts/schools, and all grantees must obtain matching funds from the private sector. In FY15, i3 was funded at $120 million. Since 2010, ED has awarded over $1 billion to 143 grantees that have secured over $200 million in private sector contributions.

The i3 program uses a three-tier evidence framework to direct larger awards to projects with the strongest evidence base and to support promising projects that undertake a rigorous evaluation:

- Development grants support the development and testing of evidence-based practices that merit systematic study. These grants support new or proven practices for addressing widely shared challenges in education. Since 2010, 98 development grants have been awarded, ranging from up to $3 million to $5 million each.

- Validation grants support the expansion of projects that are backed by moderate evidence, to either the regional level or national level. Since 2013, 39 validation grants have been awarded, up to $12 million each.

- Scale-up grants support the expansion of programs with strong evidence of effectiveness. Since 2010, six Scale-up grants have been awarded, ranging from up to $20 to $50 million each.[7]

Impact of i3

To date, nine final impact evaluations of i3 projects have been released. A 2015 evaluation of KIPP charter schools found positive, statistically significant, and educationally meaningful impacts on 1) reading and math achievement in elementary grades, 2) math, reading, science, and social studies achievement in middle grades, and 3) student achievement for students new to KIPP high schools. A 2015 report on Success for All (SFA) found that SFA is an effective vehicle for teaching phonics at the second grade level and that students entering kindergarten with low preliteracy skills registered significantly higher scores on measures of phonics in grades K-2, word recognition, and reading fluency than similar students in control groups in grades K-2. A 2015 evaluation of Teach For America (TFA) found that first- and second-year corps members in elementary grades were as effective as other teachers (with an average of 14 years experience) in the same high-poverty schools in reading and math, and a sub-analysis focused on grades pre-K-2 showed students of TFA teachers gained an additional 1.3 months on measures of reading skill relative to other students in the same schools. Findings from a final report on the Children’s Literacy Initiative (CLI) demonstrate that kindergartners and second graders score significantly higher on early reading tests than other students, and that CLI had a significant positive impact on the quality of teachers’ literacy instruction in grades K-1. According to ED, for grants made between 2010 and 2013, all 35 Validation grantees are on track to have evaluations that meet the required WWC standards, and 76 of 77 i3 Development grants will produce emerging evidence for improving student outcomes, with a majority meeting WWC standards.[8]

FIRST IN THE WORLD

The First in the World (FITW), administered by ED, supports the development and evaluation of innovative strategies designed to improve college completion, particularly for high need students. FITW expands the database of evidence-based strategies for postsecondary education and seeks to foster new ideas for making higher education more affordable. FITW was funded at $60 million for FY15.[9] In FY14, ED awarded $75 million through four-year Development grants, $20 million of which was set aside for minority-serving institutions. In FY15, FITW awarded two Validation grants and 16 Development grants.

FITW uses a multi-tier structure that links the amount of funding that an applicant may receive to the strength of evidence supporting the efficacy of the proposed project:

- Development Grants: Development grants support new or proven practices for addressing shared challenges in postsecondary education. These grants are awarded to programs that: (1) improve teaching and learning; (2) develop and use assessments of learning; (3) facilitate pathways to credentialing and transfer; and (4) implement low cost-high impact strategies to improve student outcomes.[10] In FY15, $20 million is available for 6-8 four-year grants at an average size of $1 million to $3 million.

- Validation Grants: Validation grants support the expansion and replication of programs that demonstrate moderate evidence of effectiveness, on a larger scale, such as other institutions of higher education. These grants are awarded to programs that: (1) improve success in developmental education; (2) improve teaching and learning; (3) improve student support services; and (4) influence the development of non-cognitive factors.[11] In FY15, $40 million is available for up to 5 four-year grants at an average size of $6 million to $10 million.[12]

Impact of FITW

The FITW program is too new to identify specific impact. As of 2015, 42 grants have been awarded to institutions of higher education, including 11 minority serving institutions. Every grantee must conduct an evaluation of its interventions to assess effectiveness.[13]

TEEN PREGNANCY PREVENTION PROGRAM

The Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP), administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Health (OAH), provides federal grants on a competitive basis to support innovative and evidence-based programs that reduce teen pregnancy rates particularly in high-risk communities. Up to 10 percent of funds can be used for training, technical assistance, and evaluation. TPPP was funded at $101 million in FY15.[14]

TPPP awards grants through a two-tiered system:

- Tier 1 Grants: Tier 1 grants support the replication of evidence-based programs that are proven to reduce teenage pregnancy or related risk behaviors, and comprise 75 percent of the funding administered by OAH. Tier 1-funded programs support a wide range of models identified by an independent evidence review to have demonstrated positive results after being rigorously evaluated (the number of programs on this list has grown from 28 in 2009 to 37 in 2015). Seventy-five Tier 1 grants were awarded to TPPP’s first cohort for FY 2010-2014 at an average size of $1,000,000 annually.

- Tier 2 Grants: Tier 2 grants support the development, replication, refinement, and testing of additional models or adaptation of Tier 1 models in new settings for reducing teenage pregnancy and comprise 25 percent of the funding administered by OAH.[15] Twenty-seven Tier 2 grants were awarded to TPPP’s first cohort at an average of $925,900 annually.

TPPP Impact

The FY 2010 – 2014 grantee cohort is rigorously evaluating 16 replications of evidence-based programs (Tier 1) and 18 new and innovative programs to prevent teen pregnancy (Tier 2). In addition, there are several federally-led, multi-site evaluations underway. These grantees are in the process of finalizing evaluation results. According to the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, the teen birth rate in the U.S. has declined by 29 percent since the implementation of the TPPP in 2010, which is roughly double that of any other decline over a four-year period.[16] While it is not realistic to associate all the success to TPPP alone, it has contributed significantly to the use of proven approaches to reduce teen pregnancy.[17] To date, TPPP has provided funding to 102 grantees working to reduce teen pregnancy through evidence-based approaches in 39 states and Washington, DC. Since its creation in 2010, TPPP has partnered with 3,000 community-based organizations and trained over 7,000 professionals to serve more than 140,000 people each year. A total of 81 additional TPPP grants were awarded to the latest cohort of grantees in July 2015. These 81 five-year projects are expected to serve more than 290,000 youth each year (1.2 million in total).[18]

MATERNAL, INFANT AND EARLY CHILDHOOD HOME VISITING PROGRAMS

The Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV), administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, supports the development and expansion of evidence-based home visiting service delivery models. MIECHV programs provide a range of health and child development services in-home for families for up to five years. As a provision within the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, $1.5 billion was available for from FY10 to FY14. The program was extended for one year in FY15, and extended again in H.R. 2, the “Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015,” which includes a two-year extension of MIECHV at $400 million annually through FY17.

MIECHV competitive and formula grants are awarded to individual states, with each state required to undergo rigorous evaluation of its programs. MIECHV awards two types of grants:

- Formula Grants support the development of evidence-based home visiting models that are designed to: (1) strengthen and improve the programs and activities carried out under Title V of the Social Security Act; (2) improve coordination of services for at-risk communities; and (3) identify and provide comprehensive services to improve outcomes for families who reside in at-risk communities. To date, 105 formula grants have been awarded.[19]

- Competitive Grants support entities that demonstrate continued success in implementing home visiting programs that are ready to be scaled statewide. States could apply for development and/or expansion grants depending on the status and scope of their current capacity to implement an evidence-based home visiting system. Grantees must implement programs in high-risk communities. To date, 143 competitive grants have been awarded.[20]

MIECHV Impact

In FY15, approximately 115,500 parents and children received in-home care in 787 counties across all 50 states, twice the amount reported since the program’s inception.[21] According to a 2014 report by the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness team at HHS, among 19 models assessed for impact, all programs demonstrated success in at least one of the following areas; (1) Child Development, (2) Family Economic Self-Sufficiency, (3) Maternal Health, (4) Reductions in Child Maltreatment, (5) Child Health, (6) Linkages and Referrals, (7) Positive Parenting Practices, and (8) Reductions in Juvenile Delinquency, Family Violence and Crime.[22] The Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation (MIHOPE) is a legislatively mandated, large-scale evaluation of the effectiveness of home visiting programs funded by MIECHV. It will systematically estimate the effects of four MIECHV home visiting programs across a wide range of outcomes and study the variation in how programs are implemented, as well as a cost study. Although final results are due in 2018, a report released in early 2015 detailed state needs assessments, characteristics of the models being used, and family demographics.

DEVELOPMENT INNOVATION VENTURES

The Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) fund, administered by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), supports innovative global development ideas that demonstrate the ability to scale cost effective models that improve lives. Through a three-tiered grant model, DIV harnesses the innovation of both traditional and non-traditional partners across the globe to address modern challenges in international development. DIV was funded at $21.6 million in FY15.Development Innovation Ventures

DIV awards three types of grants:

- Stage 1 Grants support the initial testing of a development idea in order to prove the viability and impact of the concept. Stage 1 grants provide $25,000 to $150,000 in project funding that may be used for up to two years.

- Stage 2 Grants support ideas that are prepared to be measured for overall impact, sustainability and possible scale. Stage 2 grants range from $150,000 to $1,500,000 and may be used over the course of three years.

- Stage 3 Grants support proven ideas that are ready to be scaled, potentially across multiple countries. Stage 3 grants range from $1,500,000 to $15,000,000 in funding and can support projects for up to five years.[23]

Impact of DIV

As of 2015, the DIV is funding over 60 projects in 24 countries with additional innovative projects still expected. Thus far, the DIV has generated positive impact in 8 issue areas around the globe: (1) Saving Lives, (2) Lighting the World, (3) Bringing Food to the Table, (4) Lifting People out of Poverty, (5) Helping Youth Thrive, (6) Improving Government Accountability, (7) Promoting Healthy Habits, and (8) Ensuring Access to Safe Drinking Water.[24]

BENEFITS OF EVIDENCE-BASED INNOVATION PROGRAMS

The use of a tiered-evidence approach in federal evidence-based innovation grants carries many benefits that contrast with traditional approaches. Perhaps most importantly, administering these grants requires defining the levels of evidence needed to fund programs according to their level of success (i.e., a common evidence framework). Additionally, the goal of many grants is to help programs move up tiers, meaning building greater evidence about what works and steering greater dollars toward more successful programs. Lastly, federal departments and agencies may also consider an exit requirement which allows the grantee to conduct an evaluation that is more rigorous than the evidence cited in the grant application, leading to more credible and extensive evidence. The chart below compares how these types of benefits compare to traditional grantmaking.

| Comparison of Traditional Federal Grant Programs andEvidence-Based Innovation Programs | ||

| Traditional Grants | Evidence-Based Innovation Programs | |

| Incentives for grantees to do what works | Grantees rarely have incentives to develop evidence-based approaches. | Grantees are funded according to the success of their model. |

| Learning and feedback loops | Grant processes are rarely designed to produce evidence that can be used to inform future investments or program models. | The rigorous evaluations required by evidence-based innovation funds generate shared data that can be used to scale effective approaches and inform future investments. |

| Innovation | Traditional grants rarely award un-tested approaches regardless of potential. | By design, promising innovative ideas are funded, and once validated, are expanded for wider application. |

| Incentives for producing evidence | By not awarding larger grants to evidence-supported programs, investors and providers are less incentivized to further develop evidence-supported programs. | By using the tiered-evidence model, grantees are incentivized to produce evidence to advance program development, leading to more reliable investments. |

| Resources | Funds awarded by traditional grants rarely cover the cost of rigorous evaluation. | The coverage of cost for program funding, staff, time, and rigorous evaluation is included within evidence-based innovation funds. |

| Leveraging “the crowd” | Traditional grant programs are often less able to capitalize on innovative ideas from outside actors. | Tier-based grant programs naturally harness innovative ideas by funding promising programs at various stages of development. |

| Mobilizing Capital | Limited public funds are tapped to finance traditional grant programs. | Through fundraising strategies such as match-requirements, public and private dollars can be combined to expand budgets, including through philanthropic sources. |

| Enabling Intermediaries and Grantmaking Experts | Traditional grants are awarded in a top-down fashion through a two-way model. | By working through intermediaries, evidence-based innovation funds capitalize on the expertise of well-positioned grantmaking intermediaries to more effectively disperse funding. |

CONCLUSION

Through its tiered-evidence innovation programs, the federal government has funded work in the social sector based upon evidence of effectiveness, enabling the most effective programs to be implemented across fields such as health, education and global development to support programs that are proven to make a difference. These federal innovation programs also require rigorous evaluation to determine what works, for whom, and why, thus building the knowledge base about what works. By investing in what works, limited dollars can be directed towards programs that demonstrate proven success and generate greater impact.

About the Invest in What Works Policy Series

This fact sheet is part of Results for America’s Invest in What Works Policy Series, which provides ideas and supporting research to policymakers to drive public funds toward evidence-based, results-driven solutions. Results for America is improving outcomes for young people, their families, and communities by shifting public resources toward programs, practices, and policies that use evidence and data to improve quality and get better results.

End Notes

[1] The Workforce Innovation Fund also served as an evidence-based innovation fund prior to being subsumed within the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014.

[2] This information comes from the Social Innovation Research Center, “Social Innovation Fund: Early Results Are Promising.”

[3] This information comes from the White House website, “Improving Outcomes through Pay for Success.”

[4] This information comes from the SIF Pay for Success webpage, “43 State and Local Governments and Nonprofit Organizations Selected to Receive PFS Funds and Services.”

[5] This information comes from the Corporation for National and Community Service, “About the Social Innovation Fund.”

[6] This information comes from the Corporation for National and Community Service, “About the Social Innovation Fund.”

[7] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Education website, “Investing in Innovation Fund (i3) Awards.”

[8] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Education, “FY2016 Department of Education Justifications of Appropriation Estimates to the Congress, Innovation and Improvement.”

[9] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Education, “First in the World.”

[10] This information comes from the Federal Register website, “Applications for New Awards; First in the World Program-Development Grants.”

[11] This information comes from the Federal Register website, “Applications for New Awards; First in the World Program-Validation Grants.”

[12] This information comes from the Department of Education website at http://www2.ed.gov/programs/fitw/funding.html.

[13] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Education, “FY2016 Department of Education Justifications of Appropriation Estimates to the Congress, Higher Education.”

[14] This information comes from the Federation of American Scientists, “Teenage Pregnancy Prevention: Statistics and Programs.”

[15] This information comes from the National Campaign website, “It’s About Results: What You Need To Know About The Evidence-Based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program.”

[16] This information comes from the National Campaign website, ”Survey Says Plus.”

[17] For example, the Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP) is another evidence-based federal funding stream for teen pregnancy prevention, which may have also contributed to reducing teen pregnancy rates. For an overview of the various federal funding streams, see “Federal Funding Streams for Teen Pregnancy Prevention.”

[18] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website, “About Teen Pregnancy Prevention.”

[19]This information comes from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website, “Active Grants for HRSA Programs.”

[20]This information comes from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website, “Active Grants for HRSA Programs.”

[21] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program Partnering with Parents to Help Children Succeed.”

[22] This information comes from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website, “Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness-Outcomes.”

[23] This information comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development website, “DIV’s Model In Detail.”

[24] This information comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development, “Development Innovation Ventures.”