Executive Summary

On 29–30 September 2016 Results for All, an initiative of Results for America, partnered with Nesta’s Alliance for Useful Evidence to host Evidence Works 2016: A Global Forum for Government. This invitation-only forum took place at the Royal Society in London, UK, with the support of The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Evidence Works 2016 convened senior officials from government, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), and philanthropic organisations to engage in dialogue and exchange ideas about the policies and practices governments around the world are putting in place to promote the use of evidence and data in policymaking to improve outcomes for citizens and communities.

The two-day event consisted of plenary discussions and a series of breakout sessions that allowed participants to engage more deeply on specific topics and issues related to the use of data and evidence in policymaking. The gathering offered a unique opportunity for government officials and policymakers to network, laying the foundation for ongoing global dialogue about evidence-informed practice. One hundred and forty participants attended from approximately forty countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, North America, Europe, and Australia.

Why did Results for All and the Alliance for Useful Evidence host a global forum for government on evidence?

There is growing recognition that, in addition to policymaker skill and knowledge, a government’s organisational processes and practices play an influential role in promoting the use of data and evidence. The forum was an opportunity for policy leaders to share experiences, including challenges, solutions, and lessons learned in establishing strategic approaches for promoting evidence-informed policymaking. Our goal is to help advance the adoption of evidence-informed policymaking across the globe to improve outcomes and the quality of life for all people.

This summary highlights the challenges and issues in evidence-informed policymaking discussed at the forum, as well as some of the key findings and points of view expressed by participants.

1. Government needs diversity of evidence

No single type of evidence will answer all government challenges. We need a diversity of approaches—not just evaluations of programmes that assess what works, but a wider range of data and analysis. We learnt about using behavioural insights in Asia, socioeconomic impact assessments in South Africa, cost-benefit analysis in Chile, economic modelling of manifestos in the Netherlands, and performance data for the Big Fast Results initiative in Malaysia. The evidence has to match the policy question—and one source of evidence will not be enough.

Evidence-based medicine is often taken as a model for policymaking. But even there, growing interest in looking beyond the traditional randomised controlled trial is fostering new methodologies using big data that will transform the methods of evaluation. The traditional methods are often not fast enough for policymakers. As one participant said, ‘A two-year cycle [for an evaluation] is hopeless.’ We need more timely data for political purposes, and analysis of real-time data may be more useful.

However, we also heard how slow policymaking can help gather public support for controversial and costly initiatives. Faster does not always mean better. One member of parliament reminded us that there are many public servants who don’t always want quick wins, but rather to deliver what’s best for the country. Rapid evidence may deliver the wrong lessons. Sometimes it takes a long time to see if a policy has worked or failed. And getting good data out of ministries is not easily done quickly. When it comes to more controversial policies, a slower, more considered evidence-gathering process can help get the public on board.

Open consultation with citizens and voters may be a vital supplement to research and data. Some policies may call for a measured, consultative, or transparent approach, for example, in considering the pros and cons of nuclear energy in South Africa, a country where consultation is embedded in the constitution. In Australia, the Productivity Commission never runs evidence inquiries shorter than three months to ensure that detailed inquiries on major issues are given plenty of opportunity for everybody to respond.

2. Independence versus proximity: How close should evidence suppliers be to the centre of power?

To maintain credibility, there is value in keeping some distance between evidence production and government. Independence gives extra authority to evaluation or analysis of policy. Legislation in the Netherlands, for example, prohibits ministers from giving the Central Planning Bureau instructions on what to do, even though they are located in the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Their rigorous independent evidence reviews are highly respected by all political parties. Using external peer review outside of government can also be useful. In Malaysia, third-party foreign stakeholders vet the work of gathering evidence alongside government staff.

Independence is also about having the strength to tell political higher-ups that their project or policy is not working. As one delegate put it, technical people need to take an ethical stance and avoid merely telling leaders what they want to hear. It’s a challenging task, but we can learn from the motto of medical practitioners: ‘First, do no harm.’ We need leadership on this front at every level—from civil servants and from politicians. One member of parliament said she thought it was her job to be an ‘insider pushing for government to think about evidence’.

But independence has its limits. Using external consultants and outside voices may mean loss of ownership. Government staff may be more likely to act on evidence they have collected themselves. One participant stated: ‘If you engage the external consultants to do the evaluation, they produce a report, some of which will be denied.’ Participants from Sub-Saharan Africa spoke of keeping the supply of evidence closer to home, rather than using evidence from donor countries or foreign bodies like the World Bank or United Nations. Despite the public benefits of a more transnational ‘what works’ function, participants were more interested in local translation of international evidence, not more evidence from foreign organisations.

3. What is the best way to communicate evidence, including negative findings?

Evidence of failure can also have a positive side. One participant noted that the crisis in economic productivity in Australia in the 1990s ‘attracted government’s attention to the holders of data and the analysts’. We can all learn more from failure than from success, he said. A heated political debate can also be a good thing. As one departmental director said about the debate over unemployment in his country: ‘The political marketplace is so intense, it has created a conducive environment for evidence . . . and we want to take advantage of that.’

Discussing negative findings may be hard. But what about communicating more positive insights from research and data? It is important to make briefings brief and adapt your message to your audience. We heard from Malawi that three levels of communication are needed: one page for the minister—a short briefing that facilitates talk; three pages for the program manager; and then a full report, twenty-five pages or more, for the technical people. But it’s not an easy task to pare down a large body of evidence, and technocrats may need to be trained on how to write concise policy briefings. The report should be in language that the politician understands. Catchy titles can help attract attention and avoid talking only to like-minded individuals. For example, in the United States, the Moneyball for Government campaign used the language of baseball, rather than the dry language of data. Visualising evidence is another way to communicate; an example is the UK’s Education Endowment Foundation’s toolkit, which summarises international reviews of evidence of what works in the classroom.

But as one politician from Africa reminded us, it is not just about how it’s written, it is making sure that there is demand for evidence in the first place.

4. How to encourage demand for evidence among politicians

To encourage greater demand for evidence, some countries make sure that ministers and senior staff agree on what topics to look at. Organisations like the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) help create demand for evidence by asking policymakers what evidence they need and then filling in the gaps. Some of the choice of data and evidence comes from the very top levels of government. The cabinet in Uganda approves the four-year evaluation programme there. In Colombia, the president picks which indicators are the most relevant to him. Colombia can’t force policymakers to listen to the evidence, but getting this support from the start helps to embolden them. Participants commented on the overall difficulty of moving from a focus on evidence production to a culture that encourages demand for and use of evidence.

Encouraging scrutiny is one way to nudge government toward using evidence. Twice a year in Uganda there is an assessment of the performance of all local and national government. A report is presented to cabinet ministers on what exactly is working and what is not. Such assessments mean that governments need to look at their own evaluations, but also learn from international evidence. Scrutiny can also come from civil society. For example, in Kenya, the nonpartisan Mzalendo (literally ‘patriot’ in Swahili) scrutinises the performance of parliamentarians. They publish regular reports for all of the electorate to see. This can be an incentive for parliamentarians to move from opinion-based to evidence-based decision making.

But in addition to alerting politicians that their performance is being scrutinised, they also need networks of support to understand and engage with evidence. After a meeting of parliamentarians from twenty countries in Cameroon in 2014, networks of politicians in legislatures were set up and encouraged to create their own national bodies, such as Kenya’s Parliamentary Caucus on Evidence-Informed Oversight and Decision-making. Training is also vital to help politicians interpret evidence, and they need good libraries and information services, which are often weak in some countries. Those outside the government can help, such as the Swaniti Initiative in India, a nonpartisan organisation that helps link parliamentarians with data.

A key to success is getting the timing right. A member of parliament from Africa pointed out the value of helping to educate recently elected parliamentarians who are new and green. The Netherlands Central Planning Bureau garners early influence by checking the economic evidence behind the manifestos of all political parties, including ones not yet in power. So before candidates even start to run the country, their ideas have been evidence-checked. Once parties are in power, evidence providers should continue to seek windows of opportunity. One participant from South Asia told us about receiving a phone call from a local district official who had two weeks to allocate a budget and wanted data on how to spend it. As several participants noted, evidence providers need to be ready for such opportunities, which present a ‘tremendous space for data to come in’.

Budgeting and financial scrutiny can provide valuable opportunities for demanding evidence, and legislatures can be important players. As one politician told us, the budgetary process is crucial as ‘that is where everything begins’, and in parliament ‘ we are the ones who approve the budget’. Outside of legislatures, government institutions of finance can also be crucial to gathering evidence. The whole drive to see more results from budgets in places like Chile and the Philippines has created a demand for evidence. For emerging economies or countries undergoing austerity measures, there is pressure to get the most from public resources. Evidence can point to where best to allocate scarce funding. This may not happen overnight. In Chile, it took decades for this evaluation culture to arise. But now Chilean government officials also have direct financial incentives; staff can get an extra salary bonus if they can show a link to more effective performance.

5. The need for public support for evidence

Persuading politicians and those controlling the money is not enough. In democracies, we also need to persuade the public. ‘In order to actually get politicians to care, you have to get the public to care’, as the head of one nongovernment body put it. Voters should be voting for desirable priorities and outcomes, such as better health, improved schools, and more jobs. ‘Where evidence comes in is finding the best way to get there.’ One government official voiced the concern, ‘If politicians start to tell us the mechanism of how to get from A to B, then there is no room for evidence.’

A European member of parliament told the forum that we shouldn’t shy away from the fact that evidence does not give easy answers, stating: ‘Democracy is about controversy, and good science is also about controversy.’ We need to improve the evidence culture and ‘have more evidence-based discussions in society as a whole—in schools, in business, and other dimensions’. We need to consider shifting the debate to focus more on ‘critical thinking and about the process, and less about finite fact’. This needs to be taught in schools, and it needs to be understood that there is an ‘ongoing evolution, and that there is never one fact, and that the results of research are always changing’.

Unfortunately, examples of evidence abuse by governments can become rallying points for grassroots public campaigns, such as the proposed cancelling of the National Long-Forum Census in Canada. According to one participant, ‘this nerdy, obscure issue actually became a huge mainstream issue’. But the increasing demand for accountability creates an appetite for evidence: ‘The citizens are actually demanding that governments should deliver.’ One panellist highlighted that for a forthcoming election in East Africa, the government is ‘busy trying to collect evidence that shows whether what they promised last time around has been achieved’. Good evidence-gathering can also be a powerful tool of the democratic process itself, providing a means for listening to the electorate. The victims of land mines in Colombia, for example, were given a voice by the fieldwork focus groups and in interviews with researchers. It was a chance to hear their stories and to relay them back to politicians.

Another lesson from the Colombian experience was the need to use different communication platforms. The Colombian researchers used videos and infographics to show their findings. In Uganda, the government establishes Barazas, citizen platforms that bring on board all the citizens in a hall to discuss government performance. Other tools, such as social media, can be both destructive and very useful, but social media especially cannot be avoided. One participant noted: ‘If you don’t do it, they will do it for you.’ If evidence providers want to engage with wider audiences, they must use journalists, social media, and have an open data system. Large-scale evidence inquiries can benefit from testing the waters with the public through consultations on draft reports and public hearings to help engage the population.

6. Who to target?

It is important to have support from the top levels of government—buy-in from the president, prime minister, or director-general. But this support has to permeate down the pyramid to local government or the frontline public servant. One former government minister told us that local government is the best target, stating: ‘We got more interest in the local authorities than the national government . . . with the mayors, with the chief of districts, and their staff. We had more difficulties to convince [other] ministers [and] very high civil servants.’ Devolution of power and budgets to the local level means there is more room to manoeuvre at this level. NGOs can also help influence and empower people on the ground.

Rather than considering only one audience to prioritise, it may be better to take a multipronged approach, looking for carefully defined champions who can promote evidence use, irrespective of what level we are on. Although we need to engage with the decision makers in power, we also need support from academics. According to one participant: ‘If you don’t have the academics, you can’t produce the knowledge which is useful.’ In Rwanda, there has been a push to align research funding with government priorities. But some participants wanted academics to be free of government direction and for researchers to be the ones to determine the best questions to study. Whoever conducts the research and data collection, it should be left to domestic governments and not to ‘development partners and donors, [who] tend to call the shots.’ In one African country, 89 percent of the evaluations had been conducted by the donor’s development partners, according to one senior civil servant. But in places like Rwanda and Ethiopia, the government is actually trying to set up its own agenda and say: ‘Come and operate within this agenda.’

7. Global evidence collaboration going forward

There was a clear interest at the forum in developing an ongoing global network or community, with a particular focus on use of evidence over production of evidence. This community could provide a platform for learning between partners from across the globe. Some of this collaboration is happening already. For example, South Africa and Colombia have been learning from each other. Colombia has also been sharing its experiences with Uganda, Honduras, and Argentina. Cross-country learning might be scaled up and formalised through a coalition. There was also interest in South-South connections—between Latin America, Asia, and Africa—bringing more solutions, real solutions to the table in an exchange of ideas.

Looking at what other countries are doing is a way of benchmarking one’s own performance and fostering political will for change. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provided a frame of reference for African countries to compare themselves with each other. But some good ideas will not travel well across borders. One participant noted: ‘A program [that] worked in a certain country may be different from the way it would work for your country.’ We have to be sensitive to different geographies, demographics, and socioeconomic circumstances. As one senior official noted, ‘Context matters . . . but there is much more eagerness to learn from other countries, from how things are working.’

Some participants emphasised that we should not reinvent current partnerships within sectors or regions. The suggestion was made to ‘build on what we already have’, including the work of initiatives and groups such as Cochrane, the Campbell Collaboration, the Africa Evidence Network, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), the World Bank’s CLEAR Initiative, the Global Parliamentarians Forum for Evaluation, and others. It was also suggested that we should identify local champions and work with those people. Networking and face-to-face meetings are important, but capacity for such linkages is limited in many countries and resources are needed. Above all, our focus should be, as one participant put it, ‘partnerships, partnerships, partnerships.’

Table of Contents

Programme

Session Summaries

Summary of Evidence Works

Map

Additional Resources

Session Summaries

Evidence Works 2016 consisted of panel discussions in plenary and small-group breakout sessions held over two days. Thematic building blocks included the role of leaders and champions in driving a results agenda; the organisational and institutional structures governments are putting in place to promote the use of data and evidence and to build a culture that supports innovation, experimentation, and learning; the inherently political dimension of evidence-informed policymaking; and the role of networks and third-party organisations in promoting the use of evidence.

Following rich discussions over the two days, the closing plenary session gave participants an opportunity to share new knowledge and final thoughts on how to encourage and sustain continued dialogue. Participants formed new contacts and relationships and expressed interest in exploring the potential for a global network or community to advance evidence-informed policymaking.

Thursday, 29 September, Panel Sessions

Welcome remarks

Michele Jolin, CEO, Results for America, USA, and Geoff Mulgan, Chief Executive, Nesta, UK, provided the opening welcome to Evidence Works 2016. In their remarks, they described the overall objectives as (1) to explore the ways in which governments are building and incentivising demand for evidence and (2) to better understand where governments need support in promoting the use of data and evidence in policymaking and to solicit feedback from participants on the need for a global coalition or community to continue to dialogue and exchange ideas. They also encouraged participants to reflect on the importance of empathy in the policymaking process—to think beyond evidence to the citizens impacted by the social and economic changes that decisions bring.

Getting results

Session highlights

- Evidence needs vary at different stages of the decision-making process. Context—whether it is the stage of policy process, organisational capacity, or resource availability—is critical to understanding and defining evidence. Some countries or initiatives prioritise the use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), but the broader definition of evidence is more applicable to different country contexts.

- Governments face the challenge of moving beyond the collection of data and production of evidence to understanding how data and evidence can be used. Data and evidence have to be packaged and framed in a way that is accessible to policymakers. Beyond the framing, policymakers also need to understand the value of evidence and have the incentive to use it.

- Governments and external partners should focus on building local capacity to support and advance the use of data and evidence in decision making. Governments specifically should invest in processes that promote evidence use, including platforms for engaging with the public.

- Countries want to learn from the experience of others who face similar challenges in promoting the use of data and evidence. This type of information-sharing is becoming more common and it can be useful way for countries to benchmark their progress. However, solutions must be tailored to respond to local problems and fit the local context.

- While champions, leadership, and commitment from the top are critical to advancing an evidence agenda, a multipronged approach that identifies champions at all levels of government is recommended. Political cycles and transitions affect the tenure of leaders, so countries may want to consider a strategy that targets leadership and policymakers at all levels, maximising the potential for institutional memory.

Overview

This session explored the approaches countries are taking to understand what works and to build evidence-based approaches, including through national policymaking. It highlighted the importance of context in defining evidence and understanding the challenges countries face in promoting the use of evidence and data, and the specific solutions they are putting in place.

The UK has made some progress in the last five to six years in building evidence-based approaches to determine what works. A good example is the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), set up only five years ago. The EEF has been conducting RCTs to better understand what works. This approach is being replicated in other areas, such as criminal justice and local growth, and although they now have a better sense of what works, there is still a lot that is not known. The UK Behavioural Insights Team is experimenting with different formats that can produce results in shorter periods of times. Importantly, these approaches are helping to generate demand for understanding what works.

The panel touched on several programs in France that have used RCTs to understand how effective the programmes are, but they also pointed to the importance of recognising the limit of RCTs. Other sectors are exploring big data, and it will be interesting to see if this type of approach can be applied to public policy.

In India, state capacity to use evidence and data varies greatly. A state like Andhra Pradesh has robust organisational and institutional data and evidence structures in place, while other states are working to build data collection infrastructure and analysis capabilities. Many states are beginning to put systems in place, but they need to take the next step of figuring out how to use data and evidence to inform priorities, program delivery, and implementation.

The panel discussed the capacity of government policymakers to demand and use evidence and the importance of putting policymakers at the centre when it comes to identifying research priorities and evidence needs. Policymakers need to be equipped with the capacity to ask the right questions and demand the relevant evidence, which will vary greatly depending on the problem at hand. The panellist from Kenya gave the example that the evidence needed to make the case for investment in education in Kenya is different than the evidence needed to inform implementation and determine the most effective model.

The session was moderated by David Halpern, National Adviser, What Works, and Chief Executive, Behavioural Insights Team, UK. Participants were Rwitwika Bhattacharya, Founder and Chief Executive, Swaniti Initiative, India; Martin Hirsch, Director General, Greater Paris University Hospitals, France; and Eliya Zulu, Executive Director, African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), Kenya.

‘The bigger issue I want to put on the table is local capacity. I think that it’s not a fly-in, fly-out thing to really engage policymakers and make sure they understand the evidence.’

Eliya Zulu Executive Director, African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), KenyaHighlights from the 2016

What Works Global Summit

Session highlights

- The first What Works Global Summit (WWGS), which took place on 26–28 September in London, UK, brought together policymakers, researchers, and practitioners to share their experiences in promoting the use of evidence, measuring impact, and facilitating knowledge translation, among other topics.

- A key takeaway from a WWGS session on the factors driving the rise in prison populations and the role evidence played in persuading states to reverse their policy was that policymakers want to be engaged in understanding and interpreting the evidence.

They are less receptive to being presented with a final analysis and solution. - Another takeaway highlighted the importance of framing and packaging evidence and data in a user-friendly way that can be understood by policymakers.

Overview

Campbell Collaboration CEO Howard White provided the highlights from the 2016 What Works Global Summit, which had taken place earlier in the week. White concluded his update with a plea to the global community to come together to coordinate and commission systematic technical reviews and syntheses and to help grow the Campbell Library.

Building a culture of evidence:

Lessons from Sub-Saharan Africa

Session highlights

- The countries featured in the session—Malawi, Uganda, and South Africa—are putting deliberate structures and processes in place to support the use of data and evidence in policies and programs and have made great progress in advancing their evidence agendas. These structures include policy dialogues, communities of practice, citizen engagement platforms, performance assessments, training of senior policymakers, packaging of communication in accessible formats, and institutionalising processes to support the use of evidence.

- These countries also face many challenges, including lack of time and resources to commission research; lack of commitment from leadership; lack of a focus; lack of trust between policymakers and researchers; weak institutional linkages between researchers and policymakers; lack of skill and knowledge at the individual policymaker level; absence of overarching guidelines on needed funding levels; lack of equipment, software and systems; poor quality of administrative data; poor quality of evaluation service providers; weak compliance culture; and lack of coordination between government departments and centres.

- The importance of building local capacity—working with the local community to address local problems—was emphasised.

Overview

Each of the panellists presented a brief overview of the approach they are taking to advance the use of evidence and data: the partnerships they are putting in place to help advance the evidence agenda, the challenges they are facing, and the lessons they are learning along the way.

Uganda has put in place a national policy on monitoring and evaluation with a plan for operationalising the policy that also identifies roles and responsibilities in information collection and offers guidance on how to use this information. While Uganda has the systems that are needed to collect data, the biggest challenge lies in translating this data and using it to inform policy and programmatic decisions. Uganda is committed to sharing experiences and learning from others and has formed many partnerships to support this effort.

Additionally, the government has hosted an evaluation week for the fourth year in a row, bringing together experts from around the world to share and learn from each other. The Twende Mbele partnership with Benin and South Africa is a new partnership that also seeks to promote peer-to-peer learning.

To learn more about the evidence initiatives in Uganda, view the presentation here.

The Malawi Ministry of Health Knowledge Translation Platform serves as an intermediary between research and policy, facilitating interaction of researchers with the policymaking process and creating broader dialogue and appreciation around research processes and evidence use. The Ministry of Health has held a series of workshops for policymakers, civilians, and academics on topics such as the use of policy briefs, systematic reviews, and engaging with the media. With support from AFIDEP, the ministry also has run a series of ‘science policy cafes’ that bring diverse stakeholders together to discuss policy issues. The 2014 science cafe helped to inform Malawi’s policy on user fees in health.

To learn more about the initiatives spearheaded by the Ministry of Health in Malawi, view the presentation here.

The South Africa Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) is relatively new but has made significant progress in building processes and practices to support evidence use. Accomplishments include quarterly monitoring of departmental annual plans. There is a system in place to monitor management performance in all 156 national and provincial departments on an annual basis. Fifty-four national evaluations have been completed to date. The cabinet welcomes evidence, and DPME has shown that a system can be created and implemented in a short time period where there is strong political will and leadership. DPME will soon be undertaking an evaluation of its evaluation system and expects to draw on the findings to improve its systems going forward. The panellist noted that the compliance culture in government as a key constraint to advancing the evidence agenda in South Africa.

To learn more about DPME’s initiatives in South Africa, view the presentation here.

The panel was moderated by Ian Goldman, Deputy Director General and Head of Evaluation and Research, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, South Africa. Panel participants were Albert Byamugisha, Commissioner and Head of Monitoring and Evaluation, Office of the Prime Minister, Uganda; and Damson Kathyola, Director of Research, Ministry of Health, Malawi.

‘In South Africa, we have a very good, very thorough audit system, but there aren’t enough consequences from the results of the audit. So there is a big issue there.’

Ian Goldman Deputy Director General and Head of Evaluation and Research, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, South AfricaFeatured discussion:

The politics of evidence-informed policymaking

Session highlights

- Politicians are faced with time constraints and have to act quickly. Evidence is one of the many factors that influence the policy process. An important goal is to convince politicians to look at the evidence. Given the sense of urgency politicians bring, it is also important to manage expectations about evidence generation.

- While difficult, it is important to acknowledge and learn from failure. Building a culture of evidence use, where use of data and evidence is part of a business-as-usual approach, makes it easier to accept failure.

- Political decision makers should engage with the public and encourage government to abandon divisive tactics that pit government and expert advisers against the press and public.

- Sometimes we expect too much from politicians, but in fact in many countries technocrats and midlevel policymakers play an influential role in the policy process.

- Policymakers need to consider different sources of evidence that are potentially more timely than evaluations or studies.

- It is important to engage with policymakers, equipping them with the tools they need to better understand the role and importance of using data and evidence to inform decisions.

- From a political standpoint and to maximise buy-in, it is best to build consensus around a problem before offering a solution.

Overview

Politics feature in every policy setting. The session explored the tension between the slow, rational research and evidence-generation process and the often fast, highly pressurised world of politics. Panellists shared some of the solutions governments are putting in place to address the constraints that politics can impose.

The panel presented the perspectives from both within and outside of government, with panellists commenting on the challenges associated with getting politicians to demand evidence. In South Africa, this demand has evolved. Politicians have come around to accepting that they need evidence and numbers to justify their policy and approach and are increasingly demanding this information. They are quick to embrace the evidence when it offers the answers they are looking for and exercise the right to reject findings that are not going their way. Technocrats have an important role to play in trying to keep the dialogue and discussion around less favourable evidence open. Finally, despite strong data systems and research institutions in South Africa, the use of data and evidence has been limited.

The Australia Productivity Commission has been in existence for forty years. It got its start as an analytic group focused on the impact of trade barriers. Implementation of some of their policy prescriptions triggered a reform process which led to several consecutive years of GDP growth. This growth caught the attention of politicians who began to pay more attention to the data and evidence backing the reforms. Success in the reforms contributed to increased confidence in and openness to evidence and innovation. This path to becoming more open about evidence prompted the observation from the Productivity Commission that it is sometimes easier to get politicians to pay attention to the evidence when things are not working. The commission’s focus is now on improving national welfare.

The session was moderated by Geoff Mulgan, Chief Executive, Nesta, UK. Panel participants were Peter Harris, Chairman, Productivity Commission, Australia; and Tshediso Matona, Acting Director-General, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, South Africa.

‘The bottom-line outcome from using fundamental analysis of data to

demonstrate what would be preferable economic and social welfare policies

for the country is that we’re in our twenty-fifth year of consecutive GDP

growth in Australia.’

‘I think, generally, the character of politicians is that they can’t live without evidence because they have mandates and deliverables to report on.’

How finance and budget offices are using data and evidence to improve resource allocation

Session highlights

- Finance and budget offices in some countries are using a range of approaches to promote the use of data and evidence, inform resource allocations, and create more effective outcomes.

- Pressure from civil society and demands for accountability help build a culture of evaluation. The media also plays an important role in pressuring for results.

- It is important to be patient and persistent, to produce evidence and wait for the right window of opportunity where it will be taken up.

Overview

The United States has a fragmented budgeting process, with major initiatives requiring the support of the president and bipartisan majorities in Congress. The administration of federal programs is highly decentralised—the federal government is limited in the evidence it can develop and the incentives it can provide to states to develop their own evidence and act on implementation. Several initiatives have been introduced to overcome these challenges. These include tiered-evidence grant programs with base funding for proof of concept grants, larger grants for projects that pass proof of concept, and even larger grants for scaling and replicating programs with significant evidence of impact. Steps have also been taken to improve the collection and use of data.

Chile has more than forty years of experience conducting government expenditure evaluations. The Ministry of Finance plays a critical role in the evaluation system, which is integrated into the budget process. All public investments have to go through a cost-benefit analysis, and the country has put in place performance indicators to track and monitor performance. To meet performance objectives, the National Budget Office of the Ministry of Finance implements a management improvement program with salary incentives.

To learn more about Chile’s evaluation system, view the presentation here.

In the Netherlands, an independent entity outside of government takes the lead in developing forecasts that inform the government’s budget, conducting policy analysis and simulations, tallying the costs of election manifestos and assessing promising policies, and examining in depth whether they work and what impact they are having. It also plays a knowledge translation role, translating research into layman’s terms for policymakers.

To learn more about the Central Planning Bureau in the Netherlands, view the presentation here.

The approach in the Philippines to results-based budgeting has been evolving over the last forty years. More recently, performance-informed budgeting was introduced in 2014 to measure outputs, while organisational outcomes to measure effectiveness were introduced in 2015. There is now a very deliberate process to track and monitor outputs and outcomes, which in turn inform the budget. A National Evaluation Policy Framework provides the overarching guidance for evaluations. The Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Bureau in the Department of Budget and Management was established to guide implementation of this framework and develop standards, policies, and guidelines to support and institutionalise monitoring and evaluation across government in the Philippines.

To learn more about results-based budgeting in the Philippines, view the presentation here.

The session was moderated by Michael Deich, Acting Deputy Director and Senior Adviser to the Director, Office of Management and Budget, White House, USA. Panel participants were Paula Darville, Head of Management Control Division, Budget Office, Ministry of Finance, Chile; Tessie Gregorio, Director IV, Department of Budget and Management, Philippines; and Laura van Geest, Director, Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Netherlands.

‘There is some civil society pressure, I would say, in terms of how you spend the money, and all of these, I think, help to build evaluation culture. But I think it’s not easy. It’s not straightforward. You cannot change from night to day.‘

Paula Darville Head of Management Control Division, Budget Office, Ministry of Finance, ChileThursday, 29 September: Breakout Sessions

Changing the culture of government to allow evidence to thrive

The session was facilitated by Ian Goldman, Deputy Director General and Head of Evaluation and Research, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, South Africa; and Nórma Gomez Caceras, Evaluation Coordinator, SINERGIA, National Planning Department, Colombia.

The role of delivery units in transforming data and evidence into results

The session was facilitated by Leigh Sandals, Partner, Delivery Associates, and Former Member, Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit, UK; and Datuk Chris Tan, Africa Region Director, Big Fast Results Initiative, Prime Minister’s Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMANDU), Malaysia.

Knowledge collaboration: Creating a new global partnership on evidence production

The session was facilitated by David Halpern, National Adviser, What Works, and Chief Executive, Behavioural Insights Team, UK; and Geoff Mulgan, Chief Executive, Nesta, UK.

Assessing progress: Practical tools for measuring government use of evidence in decision making

The session was facilitated by Tracey Brown, Director, Sense about Science, UK; and David Medina, Chief Operating Officer, Results for America, USA.

Friday, 30 September: Panel Sessions

Framing of a global coalition on evidence

Session highlights

- There is strong interest in a network or community (several participants felt the term coalition had other connotations) that is focused on facilitating exchange and dialogue around evidence use and sharing of best practices rather than one that is focused solely on evidence generation.

- It is important to clearly define the primary purpose of the network and ensure that the right mix of people working in government are involved—including innovative bureaucrats, people working at ministerial levels, practitioners, etc.

- A network could provide an opportunity to reduce the cost and burden of sharing information across countries.

- There is also some interest in developing benchmarking or scoring systems that could be used to compare country progress.

- Context is important: what works in the United States, for example, may not be relevant for India, China, or Vanuatu. It is important to share and exchange around a broad range of approaches or solutions.

- While the approaches and contexts of various countries can be seen as both an advantage and a justification for the need to have a network, these differences also raise the question about whether a network would be valuable in a practical sense.

- Consider a thematic framework, such as domestic violence or unemployment, to explore incentives, examples of what works, enablers, and how to remove barriers for different countries, so that within the framework we can learn from the experiences of others.

- Explore both the internal learning and knowledge-sharing functions of a network as well as an outward-facing advocacy role that encourages governments to use evidence.

- An evidence community or coalition should target opportunities, identifying how, when, and where governments need support to advance the use of data and evidence.

- It is important to understand the role of existing communities and how a new initiative focused on evidence could complement rather than duplicate what already exists.

Overview

The objective of the session was to solicit participant feedback on the need for a global community or network to facilitate and encourage continued dialogue and discussion on the topic of evidence-informed policymaking. The facilitators provided an overview, and participants engaged in small-group discussions before sharing with the larger group. While there was overall overwhelming support for an evidence community or network, participants felt there was work to do to define the specific objectives of the network. Participants additionally pointed out the importance of considering a broad range of evidence, including indigenous knowledge in discussions around a network. Practical and tangible components of a network could include a repository for information about country experiences in evidence use and a directory of sorts that could connect experts with others, including academics and translators.

In closing, the facilitators of the session shared that they would build on the feedback provided by participants as they continue to explore the need for a global community on evidence.

The session was facilitated by Karen Anderson, Executive Director, Results for All, USA; and Jonathan Breckon, Director, Alliance for Useful Evidence, UK.

The evidence movement: The role of networks and third-party advocacy in promoting the use of evidence

Session highlights

- Many countries are facing a dilemma of facts and lack of facts, while others face the trade-off between evidence and populist trends that appeal to policymakers.

- Outside networks can play an important role in building strategic partnerships to give increased focus to evidence use and identify practical solutions.

- The public wants to be engaged in the evidence-informed policymaking process, with a say in setting priorities, where and how to find evidence, and defining a strategy for achieving the best outcomes. But public discourse on the use of evidence to inform decisions is low. There is a perception that change takes place overnight, and issues often are framed too simply.

- A range of initiatives is needed to move the evidence agenda forward, not just a single activity or legislation.

- Putting policymakers at the centre of synthesising evidence and defining use helps build a sense of ownership.

- We should look at the evidence in terms of what works to get policymakers to pay more attention. It is important to frame and communicate evidence to policymakers in a way that is understood easily and that helps them achieve their goals.

- The bipartisan Moneyball for Government campaign in the United States, which brings together leaders from both parties to support an evidence agenda, is an example highlighting the importance of reaching new and politically diverse audiences with data and evidence.

- It is challenging to measure government success in using evidence to inform policy. Success may not necessarily mean policy change, but may be a changing narrative. Initiatives such as Show Your Workings in the UK, developed through a partnership between Sense about Science, Institute for Government, and the Alliance for Useful Evidence, and the Federal Invest in What Works Index developed by Results for America in the United States were highlighted for the work they are doing to create clear metrics for assessing government performance in using evidence.

Overview

The focus of the panel was on the role of outside organisations and networks in creating demand for and promoting use of data and evidence by policymakers to improve outcomes. It also explored the incentives being used to get policymakers to demand and use evidence.

Established in 2010, the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) was formed by researchers who were committed to reexamining the ways in which research evidence can be used to influence decision making. AFIDEP’s work is focused on finding ways to engage policymakers in evidence synthesis and use, placing them at the centre of their activities. In Kenya, for example, they have been working with Ministry of Health officials to identify gaps in data, and to better identify issues and achieve goals in sexual and reproductive health.

In the UK, there has been an emphasis on the importance of government being transparent about its evidence, influenced strongly by the Institute for Government’s Show Your Workings initiative. The Behavioural Insights Team also influenced policymakers to use evidence. The Alliance for Useful Evidence has conducted extensive research to understand the best ways to influence policymakers.

In Canada, Evidence for Democracy, a grassroots movement for evidence-based policymaking, has resulted in public accountability and engagement in the policy process, particularly around health issues.Poor decisions based on the ideology of politicians often become rallying points for the public. The previous government’s cancellation of the National Long-Form Census, for example, became a mainstream issue that brought attention to and interest in the census for the first time from people across the country. Evidence for Democracy has borrowed campaign tactics from other sectors to advocate for transparent use of evidence in policy.

The panel was moderated by Michele Jolin, Chief Executive Officer, Results for America, USA. The panellists were Jonathan Breckon, Director, Alliance for Useful Evidence, UK; Katie Gibbs, Executive Director, Evidence for Democracy, Canada; and Rose Oronje, Director, Science Communications and Evidence Uptake, African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), Kenya.

‘I think we really need to shift both how we talk about science and how we talk about evidence, more about the process of how we generate evidence, how we generate science, so that it becomes more about the critical thinking and about the process and less about this finite fact.’

Katie Gibbs Executive Director, Evidence for Democracy, CanadaBuilding national data systems to inform policy and programmes: Experiences from Colombia

Session highlights

Colombia’s evidence-agenda is driven by senior leadership and has support from the president, deputy president, deputy prime minister and minister of planning.

The uniqueness of Colombia’s statistical office (DANE) and planning office (SINERGIA) communicating and working together was applauded and showcased as a key component of their work toward a strong, integrated data ecosystem.

A question was raised about the trade-off between institutional independence of a statistical body and professional independence. In Colombia, although the director of the national statistical office (DANE) is appointed by the president and has ministerial status, professional independence is highly valued. DANE exerts independence in determining the methods and other technical decisions around statistical production. The panel expressed hope for a future statistical office that is independent, with its own budget and governance structure, and not under direct political authority of the president.

There was some discussion of the importance of globalising Colombia’s internal evaluation process, particularly making connections in the Global South with emphasis on opportunities to utilise data in post-conflict countries as new baselines are established in Colombia.

Overview

The roundtable discussion focused on opportunities to connect and build large, evidence-based data sets that can be used by decision makers to better inform the decision-making process. Representatives from Colombia’s evaluation office (SINERGIA), national statistical office (DANE), and Cepei, a think tank, held an in-depth discussion around Colombia’s experience in building and linking evidential data sets and undertaking deep analysis and investigation into key social challenges.

Colombia’s National Statistical System (NSS) consists of the Department of Statistics, which is the primary producer of statistics and coordinator of the National Statistical System, and the National Advisory Council on Statistics, which sets national priorities on statistical issues. The NSS is implemented through a National Statistical Plan, which covers a five-year period and includes strategies to guarantee the production of necessary data. It also issues standards, best practices, and technical guidelines that generally follow international standards. Another key role is assessment of statistical quality, some of which is undertaken by an independent commission. A new legal framework created a mechanism for promoting the use of administrative records to produce statistics and for the exchange of information among members of the NSS, even at the micro-data level.

To learn more about initiatives within DANE, view the presentation here.

Colombia’s results-based management and evaluation system, SINERGIA, is part of the National Planning Department. It seeks to influence policymaking through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of information through monitoring and evaluation. SINERGIA operates under a system of differential monitoring—analysing different sectors independently, but within a system that groups the indicators for all sectors as a whole. All monitoring and evaluation data are made publicly available. SINERGIA operates from a strategic agenda, meeting with all sectors to prioritise the topics for evaluation for review and approval at the highest levels of government.

The monitoring system runs at the beginning of a presidential term, as policies are implemented. It consists of twenty-three sectors, including one thousand indicators. The president of Colombia chooses the indicators most relevant to his agenda, which are reviewed at a cabinet-level meeting, and progress made on these indicators is included in an annual report to Congress.

The evaluation system consists of a five-phase process to measure the results. All evaluations in Colombia are the same: they start with the definition of the agenda and the selection of topics to evaluate. SINERGIA then sits with the sector to define the design of the evaluation and undertake the evaluation itself, which could be one of several types of evaluation—impact, results-oriented, or process evaluation—depending on the objective. In the absence of any enforcement device, SINERGIA works with the sectors in designing an implementation plan around each evaluation.

To learn more about initiatives within SINERGIA, view the presentation here.

From the Cepei perspective, concerns were raised around the need for more capacity, better technology, and additional human resources in order to use the data being produced in Colombia, citing budget shortfalls as a central constraint. The need for public-private partnerships and a multi-stakeholder process was also raised as an important part of building Colombia’s evidence ecosystem, as was the government’s work to comply with OECD standards.

The session was moderated by Ian Oppermann, Chief Executive Officer and Chief Data Scientist, NSW Data Analytics Centre, Australia. Panellists were Nórma Gomez Caceres, Evaluation Coordinator, SINERGIA, National Planning Department, Colombia; Ana Paola Gomez Acosta, Senior Adviser, National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), Colombia; and Philipp Schönrock, Director, Cepei, Colombia.

‘… [what is working is] that we are having good statistics and good monitoring, and the problem is sometimes they’re too technical for the common people to understand, and we’re not translating them… into a more simple, a more condensed way.’

The role of parliament in evidence-informed policymaking

Session highlights

- The challenge of parliamentarians representing broad segments of society and receiving data and evidence from multiple sources was discussed. It was noted that evidence does not relieve politicians from decision making but requires them to balance evidence with political considerations, which includes different realities for different people with varying viewpoints.

- The need to introduce a culture of evidence to more elected officials, particularly as they come into office, was raised as a priority. South Africa was applauded as a successful example where parliamentarians are trained in the use of evidence.

- There was agreement among the panellists on the need for more citizen education and engagement, to bring evidence discussions to society as a whole.

- It was noted that academics could be trained to produce more relevant reports that could be more readily translated into the policy process. Targeting relevant topics, having strong methodology, and producing interesting results were listed as aspects of a useful academic study. It was also noted that politicians are sceptical of independent research, as all research depends on someone or some entity and has to be put in an appropriate context.

- Boosting demand for evidence by policymakers was acknowledged as a priority, including work by outside groups to report on the performance of policymakers. It was noted that if the evidence behind decisions was made public, that level of transparency could help drive the demand and use of evidence by policymakers.

Overview

This panel was intended to highlight the perspective of the politician who is lobbied with various forms of advocacy materials and evidence from a range of outside groups and to explore the factors that influence the policy decisions they make.

In Germany, the Office of Technology Assessment at the Bundestag is staffed with scientists, working with a $2 million annual budget, to research and report on topics of priority to the committee members. These reports have helped influence policies for the Science and Technology Committee, including energy and climate policies and daylight savings time, as targeted examples.

In Kenya, the Parliamentary Caucus on Evidence-Informed Oversight and Decision-Making was established in response to a broader meeting of African parliamentarians from seven countries advocating for the use of evidence and evaluation. The representative from Kenya noted the need to better link evaluators with policymakers and noted the role of AFIDEP in training and motivating researchers in parliament to use data and evidence.

The senator from the Netherlands noted the number of policies lacking evidence and the challenge for policymakers to measure the right outcomes in evaluation. As a behavioural economist, she noted the prevalence of politicians pursuing policies that are not in line with their goals. The EU legislation mandating pictorial health warnings on tobacco packaging was presented as an example of a policy made in the absence of compelling evidence. She also noted that policymakers often fail to distinguish between correlation and causality. The Netherlands Senate has a behavioural unit that is helping to incorporate behavioural economics evidence in policymaking.

The session was moderated by Penny Young, Librarian and Director General of Information Services, House of Commons, UK. The panellists were the Hon. Philipp Lengsfeld, Member of the Bundestag, Germany; the Hon. Henriette Prast, member of the Senate, the Netherlands; and the Hon. Kirit Somaiya, Member of Parliament and Chair of the Parliamentary Energy Committee, India.

‘Evidence is the information available, but analysing that information, what evidence is, and to process and present and to come to a decision, both are equally important.’

‘Somewhere between the land of the irrational consumer and the very political politician we must make sure that our research is absolutely compelling, relevant, timely, easy to read, and that those of us who are briefing you do a really sharp job and arm you brilliantly.’

Closing remarks: Key takeaways

- Middle-income countries share many of the same challenges faced by high-income countries in developing evidence systems.

- There is a need to recognise and understand failures in addition to successes.

- Opportunities to learn and share from other experiences are of great value to countries.

- Evidence is part of the whole policymaking process, and there is a need to further understand how evidence can play a stronger role in that process.

- It is important to understand the resistance to evidence and to learn how best to advocate for the use of evidence.

- The production and use of evidence is hard work that forces policymakers to deal with uncomfortable truths.

- In addition to sharing practical tools for evidence-informed policymaking, there is a need for a global campaign to persuade people to shift their positions.

The discussion was facilitated by Michele Jolin, Chief Executive Officer, Results for America, USA; and Geoff Mulgan, Chief Executive, Nesta, UK.

Friday, 30 September: Breakout Sessions

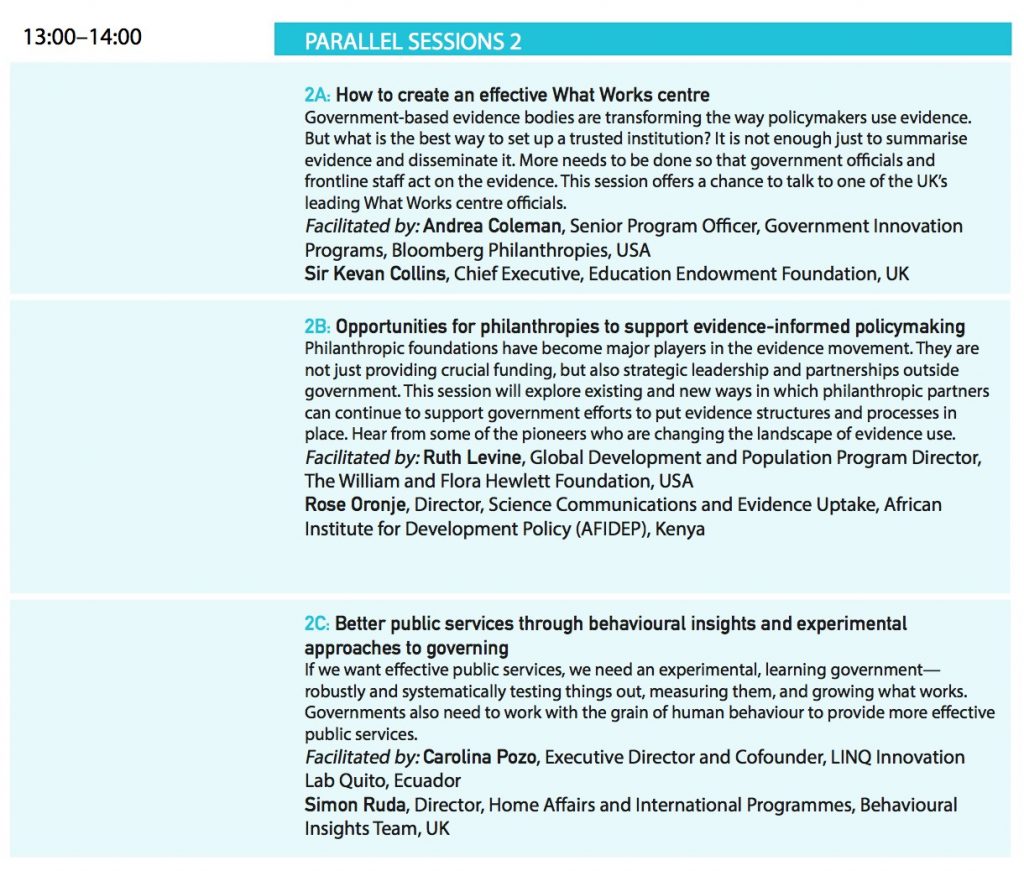

How to create an effective What Works centre

The session was facilitated by Andrea Coleman, Senior Program Officer, Government Innovation Programs, Bloomberg Philanthropies, USA; and Sir Kevan Collins, Chief Executive, Education Endowment Foundation, UK.

Opportunities for philanthropies to support evidence-informed policymaking

The session was facilitated by Ruth Levine, Global Development and Population Program Director, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, USA; and Rose Oronje, Director, Science Communications and Evidence Uptake, African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), Kenya.

Better public services through behavioural insights and experimental approaches to governing

The session was facilitated by Carolina Pozo, Executive Director and Cofounder, LINQ Innovation Lab Quito, Ecuador; and Simon Ruda, Director, Home Affairs and International Programmes, Behavioural Insights Team, UK.

From recommendations to actions: Improving the utilisation of evidence for decision making

This session was facilitated by Ximena Fernández Ordoñez, Senior Evaluation Officer, World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) and CLEAR Initiative Global Hub Team, USA; Kieron Crawley, Senior Technical Adviser, CLEAR Center, Anglophone Africa; Paula Darville, Head of Management and Control Division, Budget Office, Ministry of Finance, Chile; Sarah Lucas, Program Officer, Global Development and Population Program, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, USA; and Mapula Tshangela, Senior Policy Adviser, Department of Environment Affairs, South Africa.

Evidence Works 2016: Summary of the Programme Evaluation

On the last day of the forum, participants were sent an online evaluation survey for providing feedback on their experiences over the two days. A summary of that feedback is provided below. In total, twenty-four completed evaluation forms were submitted.

- Sixty-seven percent of participants who completed the evaluation reported that they were very satisfied with the event, and an additional 29 percent reported that they were satisfied with the event.

- Ninety-six percent who completed the evaluation reported making new connections or networks.

- One hundred percent of participants who completed the evaluation reported interest in being involved in long-term dialogue and exchange.

Comments received are summarised as follows:

1) How satisfied were you with the content, representation of topics, diversity of speakers, format, catering, venue, overall event?

- Excellent format and quality, breakout sessions were very good

- Informative and interactive, a good way of sharing and exchanging experiences

- Framing too heavily focused on UK experience and impact evaluation as primary form of evidence

- Valuable to have time in program for networking

- Topics on data production were missed

- It would have been helpful to get more specific in general

- The exclusive focus on government was much needed

2) What did you find most valuable about this event?

The two most valuable takeaways from the event were (1) networking, and (2) learning about experiences in low-, middle- and high-income countries. Other priorities included:

- Hearing from a diverse range of speakers

- Exposure to global thinking

- Learning from international best practices and from a mix of leaders

- Networking/making new contacts

- Focus on real-life experiences, not theoretical discussions on how to increase evidence use

- Getting a big picture of the issues and seeing that many countries face similar challenges

3) Following this event, do you feel there is a demand for a global coalition?

Ninety-two percent of the participants who completed the survey reported that they thought there was a need for a global coalition, with the following comments:

- Yes, but not necessarily defined as ‘coalition’—maybe a community or a network

- Yes, but needs proper defining, planning, and thought—suggestions include taking thematic perspectives

- Yes, but should not duplicate other efforts

4) Do you have any recommendations on how we can improve future events?

- Consider topics that are more scientific/economic or multidisciplinary

- Include a range of speakers/participants who could challenge the assertion that there needs to be more evidence in policymaking and invite constructive criticism

- Structure the breakout sessions so that they are less about idea generation and more about sharing of country experiences—barriers faced and the solutions they are putting in place

- More breakout sessions—make them longer and have some sessions repeat

- Frame very early on the value of different kinds of evidence for different decisions

- Give next convening a thematic overlay

- Attendance from the Middle East/Arab countries was missing

- Consider a venue in Africa or Asia

- More sessions with presentations that can be shared with others

- Involve a few more end users as well as the high-level government officials

- Share participant e-mail addresses

Global Participants by Nation

Links to Additional Information and Contacts

Results for All

Results for All Blog: Evidence in Action

Karen Anderson, Executive Director, Results for All

Abeba Taddese, Program Director, Results for All

Alliance for Useful Evidence

Alliance for Useful Evidence Blog

Jonathan Breckon, Director, Alliance for Useful Evidence

Evidence Works Global Forum Team

With thanks to